By Joshua Townsley

At 10pm on the 7th May

2015, as polling stations were closing across the UK, the GfK, NOP and Ipsos MORI exit poll was released

that predicted the Liberal Democrats would be reduced

to just 10 seats in parliament. Former leader Paddy Ashdown, who had been at the centre of the Lib Dem general

election campaign and was live on air when

the poll was released, was so shocked that he promised to publicly eat his hat

if the exit poll proved to be correct. By

the end of the night, the Liberal Democrats

were left with only 8 seats. In the early hours of the

8th May, Nick Clegg, Lib Dem leader and re-elected MP for Sheffield Hallam,

stepped up to the podium at his seat’s count

and admitted that the night had been a “cruel and punishing

night for the Liberal Democrats”. Less than 12 hours later, Clegg announced his resignation as leader,

describing the election as “immeasurably more crushing and unkind

than (he) could ever have feared”.

The Lib Dem mantra ‘Where

We Work We Win’ captured the belief that where the party’s MPs were ‘dug in’

locally, they would be very hard to beat. Two months before the 2015 general

election, Clegg declared: “let me tell you this: we will do so much better than

anyone thinks. In those seats where we are out in force, making our case loudly

and proudly, we are the ones making the weather”. Political scientists and

commentators expected that the party would hold around half of its 57 seats,

based largely on local factors such as incumbency. However, the results of the

general election were devastating for the Lib Dems, reducing the party

overnight from 57 MPs to just 8. MPs perceived to be unbeatable in their

constituencies were swept away, and the party went from serving in government

to struggling for its very survival. The near wipe out of the Lib Dems raises

questions about the existing body of research into the party’s local

electioneering. The aim of this article is to assess whether one of the Liberal

Democrats’ top campaigning strengths – incumbency - made any difference to the

party’s electoral fate in 2015.

Incumbency

An incumbent MP has the

benefit of having won the constituency once, or several, times before and can

use this knowledge and the local networks built up to secure re-election. A

‘personal vote’ is a level of support for a candidate that is particular to

that candidate, rather than the party. MPs with a high profile in their

constituency can increase this personal support over time. For instance, an

incumbent MP usually benefits from greater name recognition than their

opponents, which can be vital in securing the support of voters based on a

‘personal vote’ for the candidate rather than the national party.

Lib Dems tend to be

particularly adept at this. According to British Election Study data prior to

the general election, around 70% of respondents in Labour or Conservative seats

could name their MPs, but among voters in Liberal Democrat seats, name

recognition was 82%. These figures were relatively consistent over time.

Crucially, given the Liberal Democrats’ reliance on building a ‘personal vote’

and on securing tactical votes, Lib Dem MPs tend to be more popular among

supporters of opposition parties. This makes it easier for Liberal Democrat MPs

to distance themselves from the unpopularity of the party nationally, and rely

on personal trust and name recognition in their constituencies.

(See Nottingham’s Phil

Cowley for more on these figures, here:

http://nottspolitics.org/2014/12/09/not-love-actually).

For the Lib Dems,

incumbency advantages such as the building of a ‘personal vote’ has been a

result of necessity. Traditionally, both main parties have long relied on

class-based support as working class voters support Labour and middle class

voters support the Conservatives. The Lib Dems on the other hand, lack this

robust social ‘base’ of support, so tend to rely on building local popularity

based on the personal qualities of hardworking councillors or MPs. The ability

of Lib Dem MPs to develop a ‘personal vote’ has been essential in building

electoral strongholds.

Overall therefore, there

was significant evidence that Liberal Democrat MPs enjoyed a larger incumbency

advantage than Labour and Conservative MPs that would minimise the decline in

vote share in their constituencies. This narrative was reinforced by

constituency polling carried out by Lord Ashcroft that revealed in some seats,

such as Eastleigh, Sutton and Cheam, and Carshalton and Wallington, the party’s

vote was holding up largely due to the ‘boost’ the party received in the

polling when respondents were prompted to consider their own constituencies and

the candidates standing. This heightened the belief that popular incumbent MPs

would be well placed to survive the storm that the party faced nationally.

Analysis

This article aims to

analyse whether incumbency had any effect on Liberal Democrat party performance

at the 2015 general election. We can do this by comparing the mean decline in

vote share between 2010 and 2015 in seats with and without an incumbent MP. In May,

the Lib Dems lost a larger proportion of their vote share where they were

previously strongest. Stephen Fisher (Oxford University) had predicted this

prior to the general election using data from the British Election Study.

However, this does not mean incumbency had no effect whatsoever. If incumbency

was irrelevant, and the party’s 2015 performance was based just on its 2010

vote share in each constituency (i.e. the party's vote share collapsed most

where it was previously highest), seats with a similar vote share would

experience broadly similar decline in party vote share regardless of whether

the seat had an incumbent MP or not. In 2010, the Lib Dems polled 23% of the

vote, but only 8% in 2015. To take into account the fact that the party,

mathematically, had to lose more votes where they were previously strongest, it

is necessary to compare the mean vote share decline in seats with and without

an incumbent across seats with similar 2010 vote shares. In this way, any

incumbency effect can be unpicked from the wider trend that the party suffered

larger swings where they had higher previous vote shares.

The table below compares

the mean vote share decline for the Liberal Democrats in seats with similar

2010 vote shares depending on whether the party had an incumbent MP

re-contesting the seat in 2015 or not. The fourth column shows the ‘difference’

in the mean decline in vote share between seats with an incumbent MP standing

again, and all other seats.

The figures show that the

party did indeed experience a larger decline in vote share in seats where they

were previously stronger. But the analysis also reveals evidence of an

incumbency effect for Lib Dem MPs in 2015. Among seats in which the Lib Dem

vote share was broadly similar in 2010, there was a significant difference in

the vote share decline depending on the incumbency status of the seat. For

example, in seats such as Argyll and Bute and Bradford East where the party

polled between 31% and 35% of the vote in 2010 AND had an incumbent MP

defending the seat in 2015, the Lib Dems only experienced a mean decline of

-4%. Meanwhile, in seats such as Oxford East and Manchester Gorton, where the

Lib Dems also polled between 31% and 35% of the vote in 2010, BUT did not have

an incumbent MP defending the seat in 2015, the party suffered a huge -22.6%

change in vote share in 2015. This trend is clear across all seats

according to their 2010 vote share, including the 57 seats the party was

defending in 2015.

At the last general

election, 17.86% of sitting Lib Dem MPs had decided not to recontest their

seats. This meant that out of 57 seats the Lib Dems were defending in 2015, the

party had new candidates defending 10 of them. As a proportion of the

parliamentary party, the amount of new candidates defending held seats was

higher for the Lib Dems than both Labour and the Conservatives. This hurt the

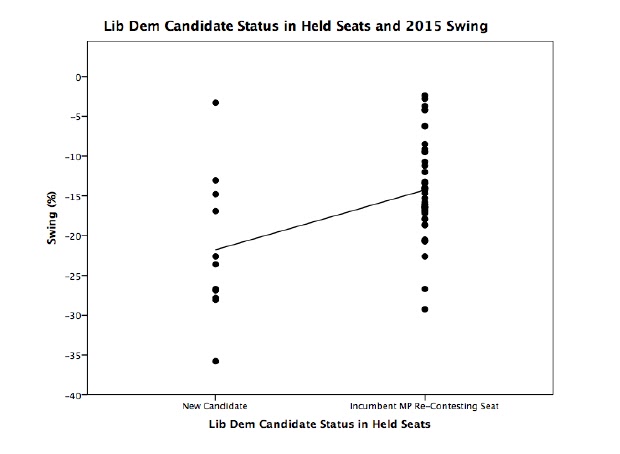

Lib Dems at the polls. The figure below compares the mean decline in Lib Dem

vote share in their 57 held seats based on whether the seat was being defending

by a new candidate replacing the existing MP (left hand column), or by the

existing MP (right hand column).

The figure shows that even

in seats in which the party polled over 51% in 2010 and won with a huge

majority, there was an 11 percentage point difference in the mean vote share

decline depending on whether the candidate in 2015 was an incumbent MP or not.

For example, in Bath the Lib Dems polled 56.6% of the vote in 2010, and

suffered a -27% swing in 2015 with a new candidate. Meanwhile in Westmorland

and Lonsdale, where the party polled a similarly high share of the vote in 2010

(60%), the incumbent MP only experienced a -9% decline in 2015. The anomaly in

the figure - the new candidate who managed to keep the party's vote share

decline to less than -4% - was Christine Jardine, who was defending the Gordon

seat previously held by Sir Malcolm Bruce against the SNP's Alex Salmond.

Figure - Mean Vote share decline for Lib

Dem Candidates by Incumbency Status (BBC Election Results, 2015).

Figure - Mean Vote share decline for Lib

Dem Candidates by Incumbency Status (BBC Election Results, 2015).

As shown in the figure

above, the decline in Lib Dem vote share tended to be much higher in seats

where the incumbent MP was standing down and a new candidate contested the

seat. The mean decline in Lib Dem vote share across all held seats was -15.7%.

Among the 45 seats in which the incumbent MP was restanding, the mean vote

share decline was slightly lower at -14.1%. But in the seats in which the

incumbent MP retired and was replaced by a new candidate, the mean vote share

decline was -21.3%. For example, in Bath the Lib Dems polled 56.6% of the vote

in 2010, and suffered a -27% vote share decline in 2015 with a new candidate.

Meanwhile in Westmorland and Lonsdale, where the party polled a similarly high

share of the vote in 2010 (60%), the incumbent MP only experienced a -9% vote

share decline in 2015. In held seats, the difference between having an

incumbent MP defending the seat and a new candidate was 7.2%, based on the mean

decline in Lib Dem vote share in both cases. While this ‘personal vote’ of

incumbent Lib Dem MPs was not enough to save the majority of seats, it was

strong enough to reduce the decline in Lib Dem vote share compared to held

seats where the incumbent MP stood down. This confirms arguments made prior to

the election that the party’s incumbency advantage is meaningless when the

incumbent MP stands down, regardless of whether the seat is held or not.

The results also seem to

confirm previous research on a phenomenon often referred to as the ‘sophomore

surge’. This describes the trend that first term incumbents tend to enjoy a

larger incumbency boost, and that this advantage does not tend to increase the

longer the MP remains an MP. There is clear evidence of a ‘sophomore surge’ for

first time Lib Dem incumbent MPs in 2015. While the mean decline in Lib Dem

vote share across all of its held seats was -15.7%, and the mean vote share

decline against all incumbent MPs was -14.1%, the mean vote share decline among

first time incumbent MPs was just -9.8%.

Therefore, contrary to

belief prior to the election, the party did in fact fare far worse in previous

‘strongholds’ in 2015. But there is evidence showing that even when previous

strength is taken into account by comparing seats with similar 2010 vote

shares, having an incumbent MP defending the seat in 2015 made a significant

difference in minimising the decline in Lib Dem vote share. The difference is

significant enough that it is likely to have saved the party from being wiped

out altogether at the 2015 general election. It is no coincidence that the 8

seats the party successfully defended all had incumbent MPs re-contesting their

seats.

Having an incumbent MP was

important, and may have saved the party from losing all of its MPs, but its

effect was essentially limited to reducing the swing – no incumbent was able to

buck the national trend and enjoy an increased vote share in 2015. Care must be

taken to avoid overstating the importance of incumbency to the Liberal

Democrats in light of this. 46 incumbent MPs re-contesting their seats were

still defeated in 2015. While the 9 first time incumbents experienced a much

smaller decline in their vote share, it was not enough to save any of them from

losing their seats. This was largely due to the small majorities each of the

first time incumbents was defending, meaning that even a modest swing away from

the party in these seats would not have saved these MPs from defeat. The party

does still enjoy an incumbency effect, which most likely prevented an entire

parliamentary wipe out, but it was nevertheless unable to prevent a ruinous

election night for the Liberal Democrats.

Conclusion

Altogether, the incumbency

effect remained strong for the Liberal Democrats, with evidence showing that in

held seats the party experienced a lower swing where they had an incumbent

re-standing, particularly a first time incumbent. Furthermore, having an

incumbent MP recontesting the seat made a difference in minimising the swing

regardless of how strong the party was previously, contrary to the theory that

the party was simply losing most where it was strongest. This seems to

contradict Stephen Fisher’s prediction, based on BES data, that the party would

do about “10 points worse in their own seats

compared with where they were previously

second”. This almost implied that the Lib Dems would enjoy no incumbency

boost whatsoever, when the results seem to indicate a ‘boost’ of between 3.7%

and 18.6%, depending on the party’s 2010 vote share in the constituency. But

this incumbency effect was not enough to stave off disaster in May.

Notes

Joshua Townsley is a PhD

researcher at the University of Kent, specialising in political campaigning and

electoral politics. For more information, see here: https://www.kent.ac.uk/politics/staff/assistant-lecturers/townsley.html

For more analysis of effect

of incumbency, see: Smith, T. (2012). Are You Sitting Comfortably?

Estimating Incumbency Advantage in the UK: 1983-2010. Electoral Studies, 32(1),

pp. 167-173.